2021’s Ransomware Perpetrator List

Black Fog’s 2021 State of Ransomware Report has named and shamed the ransomware perps that have found success so far this year:

- Darkside

- Cuba

- Egregor

- Conti

- Ragnar Locker

- HelloKitty

- RansomExx

- Clop

- DoppelPaymer

- Hotarus Corp

- Mount Locker

- PYSA

- REvil (a.k.a. Sodinokibi)

- Babuk

But we’ve taken it a step further, looking into how they do what they do so well – so that we have a better chance of fighting back.

Malware Breakdown: Common Behaviors and Tactics

They all have their own quirks that make them dangerous players, but many of the culprits on our list share certain techniques that make for successful infiltration and encryption.

Exploiting Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP)

RDP comes already installed on Windows computers and provides the ability to remotely control a computer via the internet.

Two machines – one local and one remote – must authenticate using a username and password to establish a connection. Once established, the remote user can both see and control the other device.

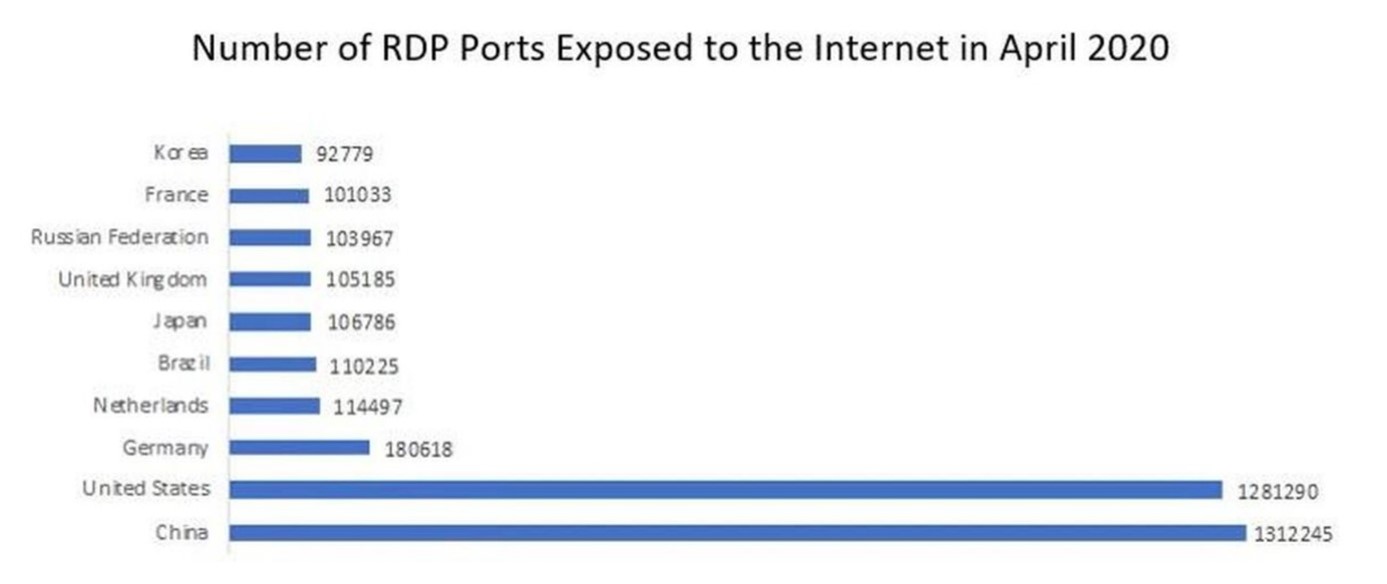

The sheer number of exposed computer RDP ports on the internet made this particular network protocol one of the biggest attack vectors for ransomware gangs in 2020, with a spike from 3 million in March last year up to 4.5 million in April – right around the time when the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic saw a shift to working from home.

Image Source: McAfee – Cybercriminals Actively Exploiting RDP to Target Remote Organizations.

But the move to remote work isn’t entirely to blame for the popularity of RDP as an attack vector. According to ZDNet, ransomware actors were already scoping out insecure RDP connections to exploit in the shift from targeting home consumers to targeting companies.

Whatever the reason, RDP exploitation is the most common attack vector for the ransomware perps on our list, who scan the internet for exposed ports and then use brute-force (the tactic of submitting a multitude of possible username-password combinations until one of them is successful) to gain RDP access.

For most, if not all, of our 2021 ransomware perps, a successful RDP logon is the first step in the infection chain. Once this initial foothold is gained, attempts to infiltrate the wider network and encrypt files.

Stopping Services and Processes

A common behavior of 2021’s ransomware gangs is to stop Windows services and processes prior to encryption.

Terminating database, backup, and mail servers (as well as antivirus software – more on this below) both ensures that their associated data can be successfully encrypted and increases the impact of the attack.

Examples:

- Conti Ransomware stops 146 Windows services that handle security, backup, database, and email.

- According to a static analysis on Mount Locker, the ransomware terminates every running process that is not on the malware’s exception list, does not run from the Windows directory, and does not belong to the ransomware.

- Ragnar Locker iterates through all running services, with the ability to terminate those typically used for the remote administration of networks by managed service providers (MSPs), such as ConnectWise and Kaseya.

- An analysis by Beeping Computer reveals that HelloKitty ransomware targets more than 1,400 processes and Windows services for termination, while Clop ransomware shuts down over 600.

- Babuk Locker, although described as ‘amateur’ by researcher Chuong Dong, features a hard coded termination list which includes services and processes that provide backup, monitoring, and mailing capabilities, including BackupExecVSSProvider, YooBackup and BackupExecDiveciMediaService; and sql.exe, oracle.exe and outlook.exe.

Disabling Anti-Virus Software

Along with the termination of services and processes, the latest ransomware variants often include functionality to disable or uninstall security software before encryption begins.

Doing so allows the malware to avoid detection and potential termination on the target system, paving the way for smooth, uninterrupted encryption.

Examples:

- Clop ransomware searches for security products installed on the victim computer, with the ability to modify registry keys via the command line to disable Windows Defender, Malwarebytes notifications, and uninstall the Microsoft Security Essentials client.

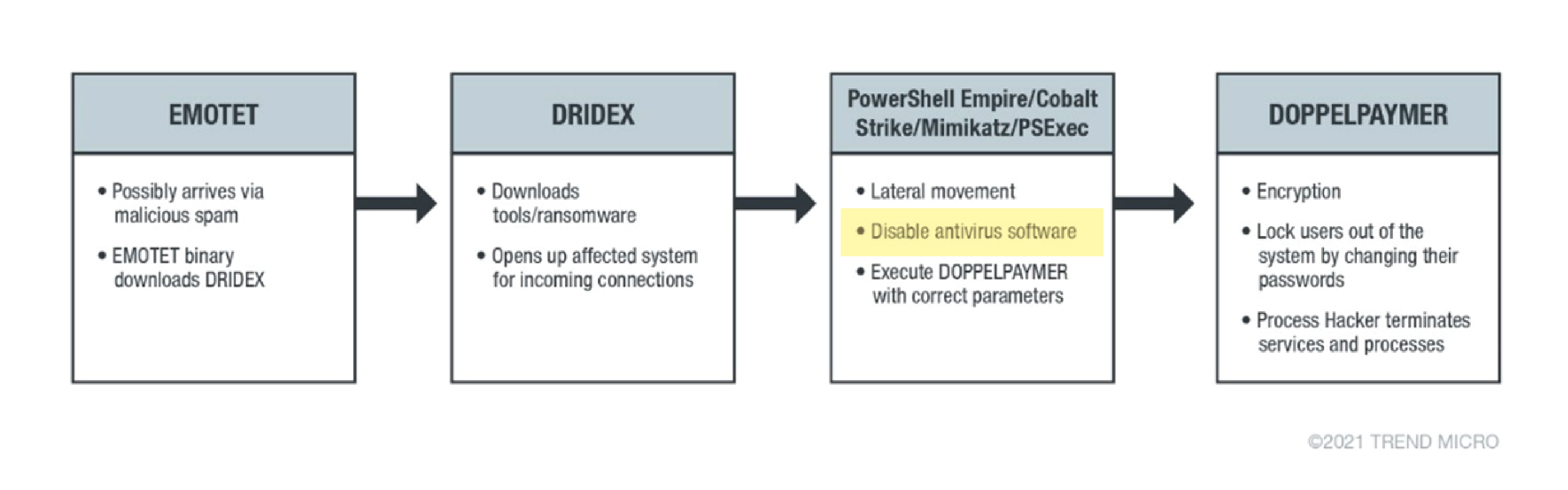

- DoppelPaymer disables security software prior to executing the main malicious code, leaving the door wide open for the encryption that follows:

Image Source: Trend Micro – DoppelPaymer Ransomware Information.

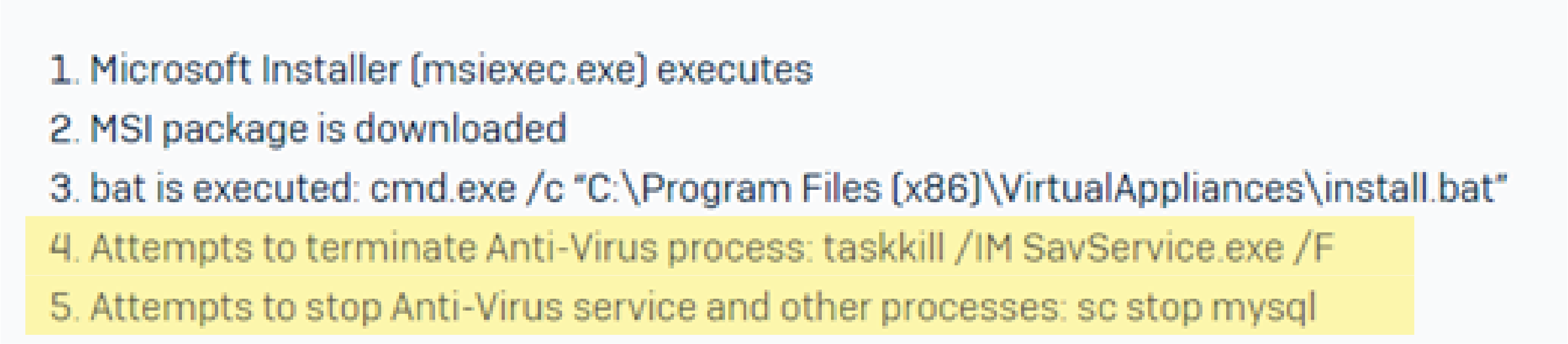

- Sophos Labs identifies the following two early stages of Ragnar Locker’s installation process:

- RansomExx and PYSA ransomware are also known for disabling antivirus solutions on target devices and networks before executing the main event.

Using (/ Abusing) the Windows Restart Manager API

The Windows Restart Manager frees up files during installation processes that may already be in use by another running service or application, so that installation can complete.

It’s main purpose is to save the user from having to endure frequent system reboots by stopping and restarting all but the critical system services.

Several ransomware culprits that have found success so far in 2021 by misusing the Windows Restart Manager API.

The process goes as follows:

- The ransomware encounters locked files during the encryption process,

- It force-terminates applications or services that are using these files by making custom calls to the legitimate Windows API,

- Once these applications or services are terminated by the Restart Manager, the ransomware can then encrypt the files that were previously in use.

The goal here is to encrypt as many files as possible for maximum impact – as the saying goes: the more, the merrier!

Examples:

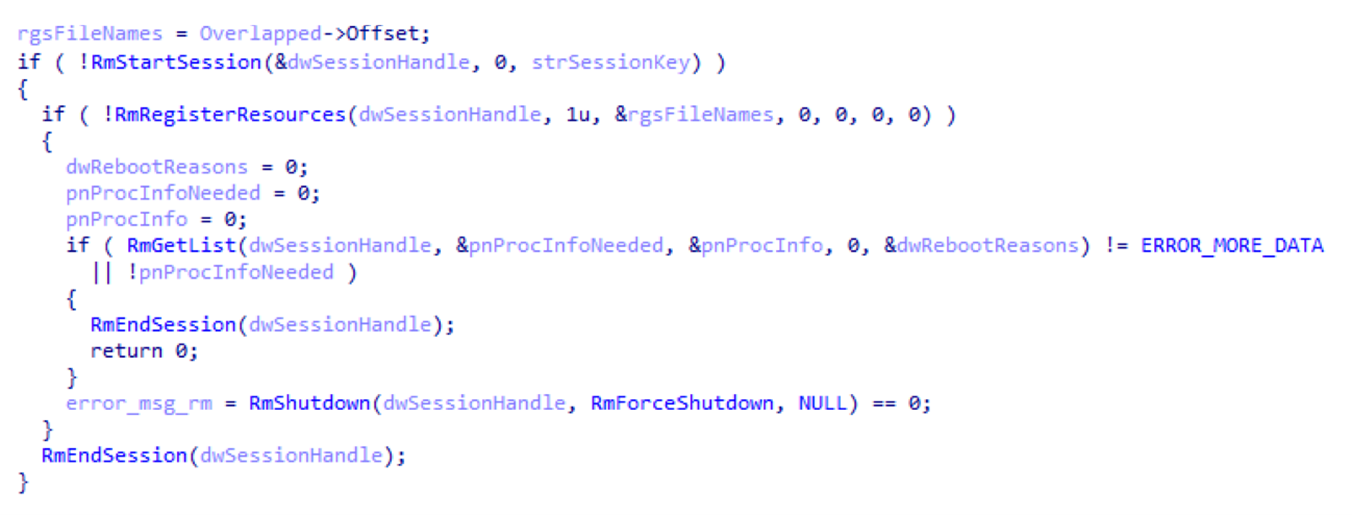

- Newer variants of HelloKitty, Clop, Babuk Locker, REvil and Conti all use and abuse the Restart Manager API when they encounter open or locked files during encryption.

- The snippet below captured by Carbon Black shows a custom Conti ransomware call to the Restart Manager on a file path:

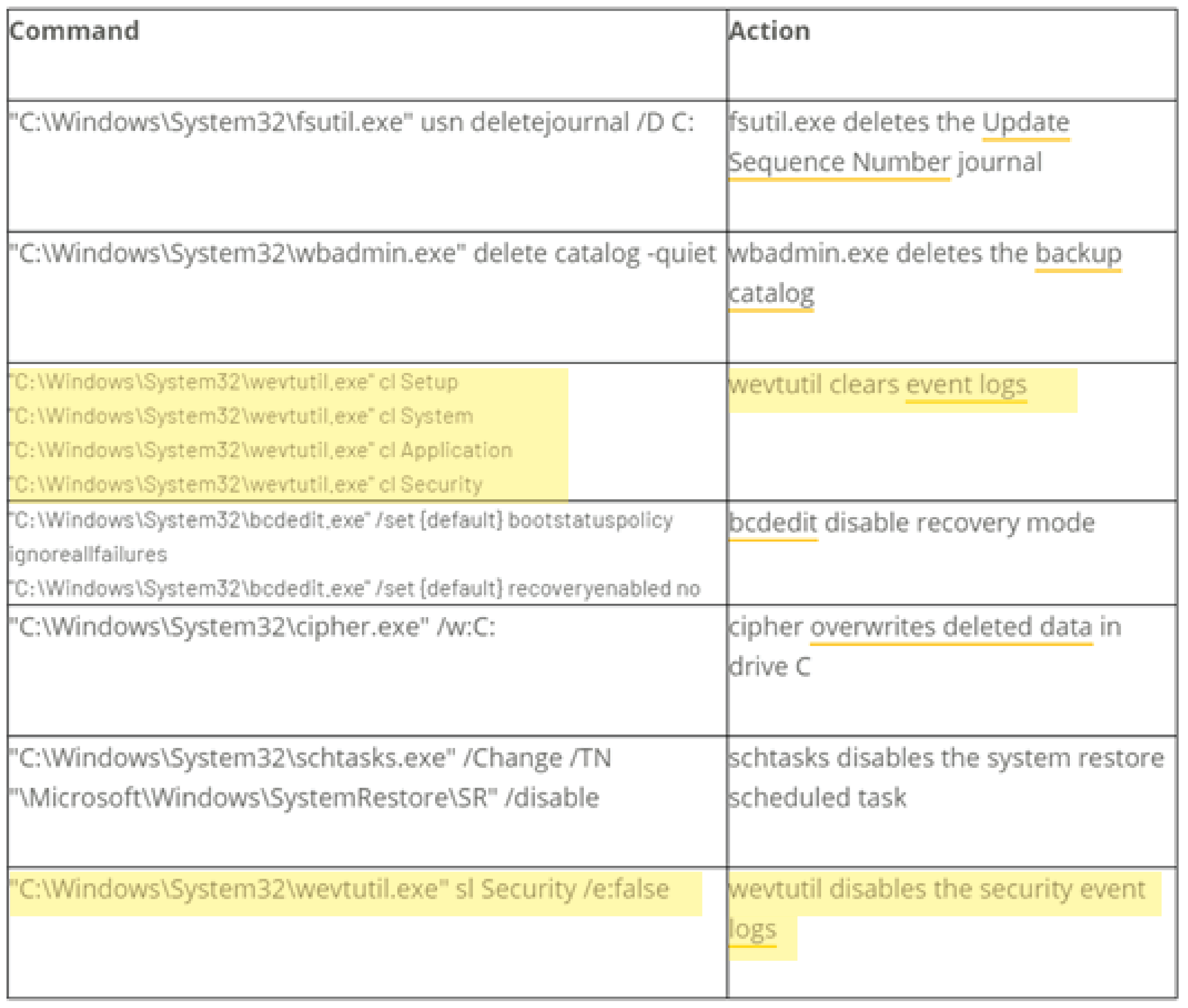

Clearing Event Logs

Windows event logs help with monitoring account activity and detecting potential threats – which is exactly why some ransomware actors ensure their malicious code disables or wipes event logs during the infection process: doing so makes the detection and tracing of unauthorized activity just that little bit harder.

Examples:

- An S2W LAB analysis of Clop ransomware reveals that, after encrypting remote shared folders, the malware then runs the following Windows wevtutil.exe Event Viewer Log deletion command which clears all event logs in Event Viewer at once:

- Cyberreason’s breakdown of RansomExx shows that the ransomware runs multiple Windows wevtutil.exe commands to clear Setup, System, Application and Security event logs, and later, disables future security event logging:

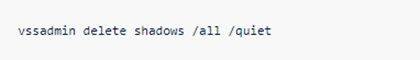

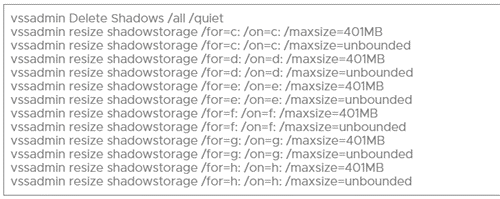

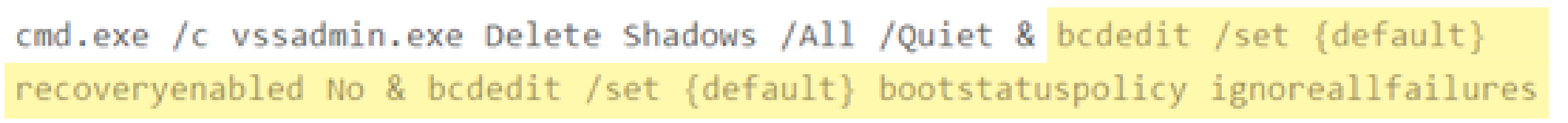

Deleting Shadow Volume Copies

Typical of most ransomware is the deletion of Shadow Volume Copies during encryption, and this year’s ransomware variants are no exception.

Shadow Volume Copies are backup copies of computer volumes that can be used to restore files if they are lost or corrupted.

Unsurprisingly, the ability to restore encrypted files is the last thing that ransomware actors want their victims to have.

Examples:

- There is evidence that most, if not all, the ransomware gangs on our 2021 perp list use the following Windows vssadmin command to delete Shadow Copies on their target system:

- Carbon Black’s analysis of Conti reveals that the ransomware uses the command above, while also enlisting the use of multiple vssadmin resize shadowstorage commands for each volume to resize their storage associations – a technique which would cause them to disappear:

- Secureworks’ REvil breakdown demonstrates how this ransomware takes deletion of shadow copies a step further by also disabling recovery mode using the extended BCDEdit command below:

Moving Laterally Across Networks

If there is one, all-important thing to note about all advanced ransomware (not just this year’s culprits) it’s that the main goal is never just the initially compromised device. The site of initial infection is simply the foothold to gain access to the rest of the network – where the really juicy stuff is.

Lateral movement is the technique of using built-in tools and protocols to gain deeper access into the target network, and that’s what sets apart the advanced ransomware of today from its simpler predecessors.

Using this technique to expand from the initial infection point often means malware can avoid detection and maintain ongoing access to the system, even if the initial infection point is discovered.

Lateral movement essentially allows attackers to increase the span of control from the initial infection site to the wider network in search of their main target: the point from which they have the most access and control, and can therefore do the most damage when encryption begins.

The Catch: Privileged Access is a Must

Looking back at the tactics enlisted by so many of this year’s ransomware perps, there is one non-negotiable required for success: administrator access.

All of their common behaviors (post-initial access and pre-encryption) require a higher level of access to the target system than that of a regular user.

Regular users are unable to stop services and processes and disable antivirus software. They cannot make custom calls to the Restart Manager API, clear and disable Windows event logs, or delete shadow volume copies. For all these tasks, elevated access is a must.

In order to gain elevated access, ransomware perps attempt to increase their privileges on the target system without authorization, in what is known as privilege escalation.

With privilege escalation fueling lateral movement, ransomware actors can:

- Increase their reach throughout devices on the network, spreading from one user to another as they search for the main target (horizontal privilege escalation),

- Increase their privileges from regular user to administrator and domain admin as they go, in order to successfully unleash the tactics described above (vertical privilege escalation).

Gaining local or domain level access is the pot of gold for ransomware actors – it allows for the control of all systems, other users, and access rights within the environment.

Keeping Up with the Cybercrims

At the heart of these common ransomware tactics is privilege escalation, so it makes sense that Privileged Access Management (PAM) should be at the heart of a good defense system.

PAM incorporates two key principles to ensure the safety of the wider network from ransomware actors attempting privilege escalation:

- The Principle of Least Privilege (POLP) – users should have the least possible privileges required to do their job,

- Just-in-time Elevation (JIT) – users only gain elevated privileges when absolutely necessary.

In a computer environment that has a comprehensive PAM solution implemented, ransomware that manages to gain that initial foothold has nowhere to go and nothing to do.

Admin By Request is a PAM solution that both prevents initial infection, and thwarts any attempts at privilege escalation.

Implementing both POLP and JIT, Admin By Request revokes users’ admin rights while still allowing them to self-elevate when they need to. Day-to-day functions can continue smoothly, in a safe and controlled environment.

Privileged activity that occurs during a self-initiated admin session is logged in the Admin By Request Auditlog, monitored by your IT admins via the software’s user portal. This means any ransomware actors’ attempts at vertical privilege escalation will be flagged and investigated from the get-go.

That is, assuming the malware can gain initial access in the first place. To do so, it first has to get past the 35+ anti-malware engines that form OPSWAT’s MetaDefender Cloud – integrated with the Admin By Request solution.

Good guys: 1; ransomware: 0.

Summary

It’s no secret that the advanced tactics employed by recent ransomware gangs are a very real threat; but recognizing and understanding what these tactics are is the best way to form a defense.

The frontline of that defense should be a comprehensive PAM solution – so you can prevent ransomware attacks before they even begin.